In my previous post I mentioned how Galloway’s originally Gaelic place-names are hidden in plain sight by their spelling. This isn’t due to ignorance on the part of the surveyors who collected the names and established their spelling. The Ordnance Survey Names Books are full of notes on the Gaelic (and Scots) etymologies of Galloway place-names. For example, a search for druim reveals that surveyors were fully aware that drum represents druim, the Gaelic word for ‘ridge’. While I think it’s interesting to see originally Gaelic place-names spelled in standard Gaelic orthography, the OS surveyors made the reasonable choice to follow local pronunciation and traditional spelling and used Drum- rather than Druim-. A rare (and I think only) exception is Druim Cheate in Tongland NX 721 588, where the surveyors selected a historical form of the name over one used locally:

“An arable hill on the estate of Argrennan where a battle was fought by the English & Galwegians against a Scotch Army under Edward Bruce it is now generally called Drumbeat, probably a corruption of Drum Cheate. […]” OS1/20/133/63 (see also OS1/20/130/31)

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

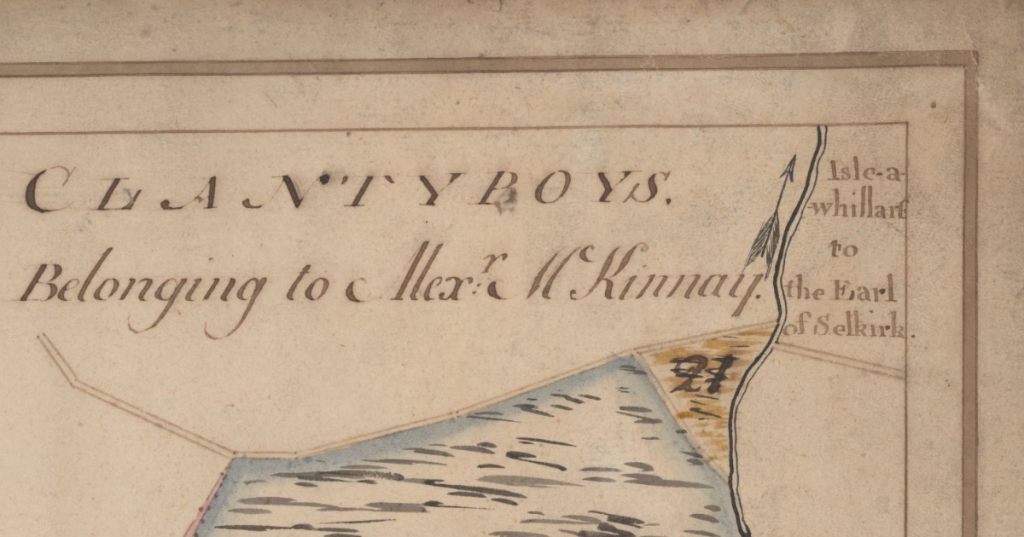

While Druim Cheate appears to be a one-off in terms of opting for distinctively Gaelic spelling, there is a group of place-names in Wigtownshire where hyphens are used to mark out the structure of originally Gaelic names. These are typically x-na-y names (x-of the-y), though Auld-taggart and perhaps a few others are of a different structure. The Name Book entries for these places give an insight into how these forms were selected. It’s interesting to note that this way of punctuating names wasn’t an innovation of the OS. For example, Isle-a-whillart (a name that didn’t make it to the OS) appears on map No. 43 Eldrig survey’d 1778 by John Gilone and in the 1797-1798 Farm Horse Tax Rolls: E326/10/5/296 & E326/10/12/243.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

I’ve included the examples I’ve found so far below. (There are probably other names of the Auld-taggart type but I’ve not gone through the Name Book entries of every x-y name to see if there was an etymological motivation behind the use of the hyphen.)

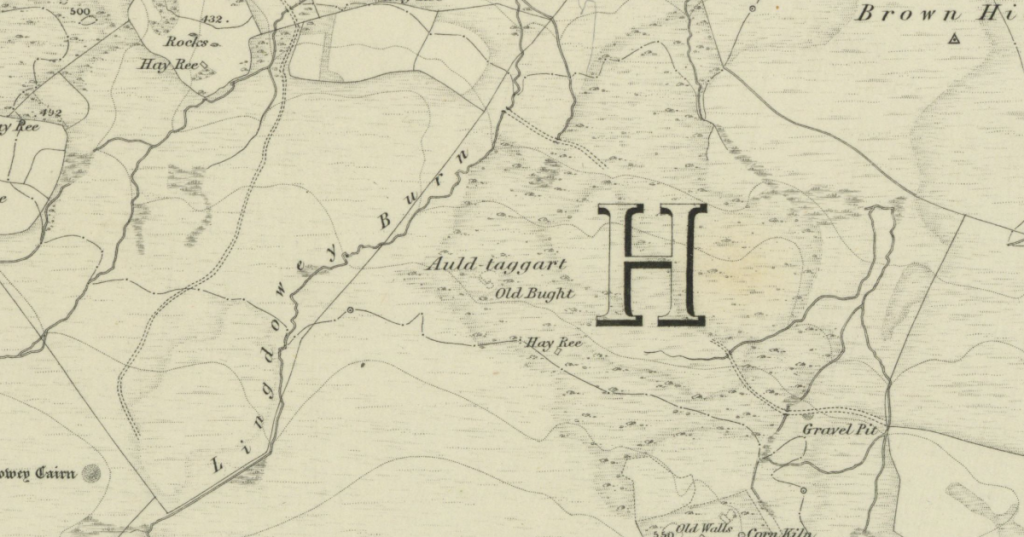

Auld-taggart, Inch NX 150 667

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Auld-taggart appears as Auld Taggart on the 2nd edition six-inch map. The Name Book entry includes Alt Taggart as a variant spelling. A scored through note says that the first element probably represents ‘Alt “height” not Auld ‘old'”. Alt Taggart is likewise scored through in the recommended orthography column. This form was supplied by George McHaffie Esqr. who, as we’ll see, is the authority for all but one of the Gaelic-y looking names listed below. The spelling Auld-taggart seems to be a nod the name’s Gaelic meaning without committing to using the Gaelic world alt (now spelled allt). OS1/35/21/27

Ballach-a-heathry, Old Luce NX 215 603

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

This is the spelling given by all authorities including, notably, an ‘old map’. OS1/35/40/4 OS1/35/40/37

Balloch-a-rody, Kirkcolm NX 015 702

OS1/35/2/52 includes both unhyphenated spellings of the name and one without any indication of the definite article -Ballaghrudy. The form adopted is the one given by George McHaffie Esqr. The entry in OS1/35/2/123 interestingly lists Balloch-a-rody as an alternative name for Ballaghendy. Ballaghendy didn’t make it to the OS and is an example of the many obsolete Gaelic place-names waiting to be recovered from the Name Books.

Cairn-na-Gath, New Luce NX 212 674

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

The unhyphenated Cairnagath is scored out and Cairn-na-Gath adopted on the authority of George McHaffie Esqr. Incidentally, the same page in the Name Books sees hyphenated Kil-McFadgean scored out and replaced with Kilmacfadȝean on the authority of our hyphen-fan McHaffie. OS1/35/22/5

Croft-an-reigh, Wigtown NX 436 555

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Here Croft Angry is scored out and replaced with Croft-an-Reigh. Croft Anreach is one of the variant spellings listed. George McHaffie Esqr. gives three forms: one with 2 hyphens, one with 1, and one with 0. OS1/35/52/5

Ilan-na-guy, Kirkcolm NW 976 718

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

This entry for this name includes includes an interesting section on its etymology. Ilannaguy is scored out out replaced with the hyphenated version. More interesting is that the entry in the first column (‘List of names to be corrected if necessary’) is Isle of Guy. Was this a local translation of the name? No prizes for guessing who the authority for the hyphenated name was.

“[…] The name Ilan na guy is gaelic & signifies The windy Isle this would imply that the place was once surrounded by water and a tradition in the Country is of the same import a stream at the E[ast] side of this is said to be once the place which the water of the Sea covered at high tides.” OS1/35/2/7

Isle-na-gower, Penninghame NX 335 674

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Although Isle-na-Gower is given as the recommended orthography, the name appears without hyphens on the 1st edition of the map; they reappear in 2nd edition. The entry includes the definition ‘The Goats Isle’. Two spellings of the name were collected: Isley Gower from James McWalker and Isle-na-Gower from George McHaffie Esqr, who as we have seen carried a fair amount of clout. It may be that this latter form was a local alternative, but it seems more likely to be the product of an antiquarian interest in Gaelic place-names. OS1/35/29/20

Loch-na-gill, Penninghame NX 341 699

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

We appear to owe the hyphenated form here to George McHaffie Esqr as well. Loch Nagill, the form supplied by Alexander Hannay has been scored out in OS1/35/14/3. However, in OS1/35/14/42 where Loch-na-Gill is the only form given Alexander Hannay is the only authority. OS1/35/14/3 describes the loch as, “A small lake where leeches used to be obtained which are called my the peasantry gills.”

Loch-na-tummock, Penninghame NX 345 685

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

George McHaffie Esqr strikes again! Although here he agrees with Alexander Hannah in the use of hyphens. He is the authority for changing the original CH to CK. OS1/35/14/20

A task for another day would be to go through the places where George McHaffie is listed as an authority and see what his spellings were and if they were adopted. Was it just these names that lent themselves to a clear x-na-y structure? For now it’s enough to note that we owe most – though not all – of these Gaelic-y looking names to the spelling preferences of one man.

Update 29/7/23: I see that George McHaffie gives Craignawachel without hyphens. He does the same for Craignabey where others notably do give hyphenated forms. For Claddyochdow he gives Claddoch-adow; James Osborne gives Claddagh-a-doo.

Interesting observations. My impression is that the hyphen in such names was a construction beloved of Victorian era antiquaries who knew the names were Gaelic but couldn’t be arsed finding out the correct orthography for them. In truth many of the Galloway place-names could have been rendered in Gaelic orthography as the names as given by the informants were often being pronounced just as a native Gaelic speaker would have given them.

I had always thought Druim Cheate was an antiquarian copy of the place in Derry where Columba had some kind of assembly (I haven’t got the details to hand).

It would be interesting to discover a bit more about McHaffie’s background.

There is also Craigfionn near Loch Doon, the OSNB states for this one that ‘Fionn is Celtic for white’.

Robby mentions giol ‘leech’ in the Galloway book at pp. 112-113

Also Craig-an-Huirry, Ballantrae see:https://www.facebook.com/groups/1501813616755643/my_posted_content?locale=en_GB. there is the comment ‘Signifying the hill of tears, or sorrow. W. McRae’ – does he mean Creag nan Deòir or Creag an Dheòir?

Croftangry has of course been debunked as a Gaelic origin place-name

LikeLike

Thanks for Craig-an-Huirry. Ballantrae itself is ripe for hyphenating. I presume we only see it in minor names as others have well established non-hyphenated spellings.

A study of the surveyors’ knowledge of Gaelic would be an interesting project. I’m particularly interested in the glimpses they give of local thoughts about the meaning of names. A note in the entry for Craig-gork (OS1/35/25/18) says that, “The hill is supposed to derive its name from this Carig-cear – i.e. The Hen’s Rock.” Supposed by who? I wonder how many people in the 19th century identified place-names names as Gaelic. I like Mactaggart’s comment at the end of his entry for MERRICK: “hence the name Merrick, which, in the Gaelic, signifies fingers. How expressive that language must be. O! that I were master of it.”

The Name Book takes the location of Druim Cheate in Tongland from Nicholson’s History of Galloway. Drumbeat doesn’t strike me as a particularly strong match. Do you think -bate might be the same ‘drowned’ element as in Dalbeattie and Dalbate? The OS marks Floods nearby.

LikeLike

Another very interesting piece!

Druim Cheate is odd, isn’t it? I notice in the Name Book in the right-hand column, ‘Druim Cheate in Gaelic means “the field of meeting.”‘ Of course it doesn’t mean that, and, leaving aside Druim I can’t see any words for ‘meeting’ that are at all similar to *ceat – nor indeed any in Gaelic at all closer than ceath which could mean ‘cream’, but being feminine would be *Druim (na) ceithe. Druim (a’) chatha ‘battle ridge’ might be nearer the mark.

The same note continues with a quote from Nicholson’s History of Galloway 1782 vol. I p. 265, ‘Druim Cheate, now generally called Drumbeat, is an arable hill where a battle was fought between a Scottish army under Edward Bruce and the English and Galwegians. Fragments of many warlike instruments have been found and also a piece of gold which could have been a sword-hilt. A large stone on the left-hand side of the road leading to the bridge of Dee marked where the battle commenced.’

That’s not transcribed on Scotland’s Places site, but conveniently is on Canmore, with the addition ‘No additional information about the battle. The large stone was not located. There is, however, a “standing stone” at NX 7170 5920 but with no local tradition attached. Visited by OS (EGC) 16 August 1968.’

Altogether, it looks like the surveyors were taken in by some antiquarian speculation, the name was probably *Druim (na) beithe ‘birch ridge’, and ought to be Drumbeat.

Cheers

Alan

LikeLike

Thank you. Might b(h)ài(th)te, as in Dalbate (Middlebie) and Dalbeattie, be a possibility? Haughs are more likely to be ‘drowned’ than drums, but Drumbeat does sit in a floodplain. Watson (from memory) rules out beithe for Dalbate on the grounds that it would have ended up as Dalbeath or something similar. Are there other examples of beithe giving rise to rather than ?

LikeLike

Oh yes, so he does (CPNS 180), comparing it with Feabait in his home country of Ross, and Badenoch too (CPNS 118, though I’m not very convinced that’s ‘drowned’) Even if Nicholson was muddled about ‘Druim cheate’ and the battle, he may still have been correct in saying that the place was (in 1782) ‘ now generally called Druimbeat’, which would favour beithe. I’ve a hunch I have seen ‘bate’ as a reflex of beithe, though I can’t readily find examples among p-ns; the surnames Batey and Beatty (of differing origins, neither to do with birch) do get muddled together.

LikeLike

I see, in an announcement about his grandson’s Birds of Wigtownshire, ‘George McHaffie, was provost of Wigtown and the family’s town house was in Main Street (now The Bookshop).’ So Shaun Bythell might have more info about him.

https://www.the-soc.org.uk/news/94birds-of-wigtownshire-published-at-last

I guess this formidable-looking gentleman was Provost George’s son, in 1900: http://www.futuremuseum.co.uk/collections/people/lives-in-key-periods/empire-industry/defending-the-empire/george-mchaffie-and-the-caledonian-challenge-shield.aspx

Alan

LikeLike

Thanks for this.

LikeLike